If it seems as if North Korea wants us to sit up and pay attention — Don’t forget, we’re still building missiles and nuclear weapons! — that’s certainly one of its objectives.

But these tests are about a lot more.

Read MoreIt was an audacious crime characterised by its grand scale and meticulous synchronisation. Criminals had plundered ATMs in 28 different countries, including the United States, the UK, the United Arab Emirates and Russia. It all happened in the space of just two hours and 13 minutes - an extraordinary global flash mob of crime.

Millions of dollars are stolen from ATMs at the same time in 28 countries. An army of money mules stuff the cash into bags. Do they know who they are really working for? In just over two hours, the thieves take nearly $14 million - all from the accounts of Cosmos Bank in India.

The hackers are back – and they are accused of being more dangerous than ever. Their cyber-attacks are getting more sophisticated and audacious. It’s claimed they are getting away with billions. North Korea denies everything.

A special episode recorded in front of an audience in New York. What’s it like working in North Korea? How are hackers tracked in real time? #LazarusHeist

It’s a frightening prospect for an unvaccinated, undernourished nation of 25 million people. But bad news does not escape North Korea without a reason. Finally acknowledging a viral outbreak may be part of a strategy by its leader, Kim Jong-un, to re-engage with the outside world. The world should be ready to engage, too.

If it seems as if North Korea wants us to sit up and pay attention — Don’t forget, we’re still building missiles and nuclear weapons! — that’s certainly one of its objectives.

But these tests are about a lot more.

In 2016 North Korean hackers planned a $1bn raid on Bangladesh's national bank and came within an inch of success - it was only by a fluke that all but $81m of the transfers were halted, report Geoff White and Jean H Lee. But how did one of the world's poorest and most isolated countries train a team of elite cyber-criminals?

“I was terrified.” Panic in Hollywood, careers ruined and helium filled balloons sent to North Korea. President Obama makes clear who he blames for the Sony hack.

A movie, Kim Jong-un and a devastating cyber attack. The story of the Sony hack. How the Lazarus Group hackers caused mayhem in Hollywood and for Sony Pictures Entertainment. And this is just the beginning…

The most daring bank theft ever attempted? From hacking Hollywood to a billion-dollar plot. Premieres 19 April 2021. With Geoff White and Jean Lee.

My family’s wartime tale is not particularly remarkable; their harrowing experience could be told a million times over. This is not a tale of military heroism, or even one of selfless sacrifice. It is simply the story of one family of ordinary Koreans who survived the three cruel and crushing years of war that killed nearly a million South Korean civilians.

As other countries hurtle toward disaster, South Korea looks like the safer and smarter place to be. So what can other governments learn about how to handle coronavirus?

by Jean H Lee / March 27, 2020

Bong “came of age just as South Korea was making the transition to the First World and as the internet brought the world to Seoul. His influences are broad and worldly, and his movies reveal a newfound sense of empowerment and independence as a South Korean. He made a South Korean film, set in South Korea, touching on South Korean issues — but informed by techniques and inspiration gleaned from influences around the world. I’m in awe of his vision — and his strength of mind in casting aside conformism to make a film that risked the disapproval of those who seek to portray South Korea in only a positive light."

What a difference a week makes when it comes to diplomacy with North Korea.

Earlier this month, one year after the dramatic Singapore Summit of June 2018, nuclear negotiations with North Korea appeared stuck in a standstill. Pyongyang was giving friends and foes the cold shoulder as leader Kim Jong Un remained in retreat following his failed second summit with US President Donald Trump in Hanoi in late February.

Then, in the span of just a few heady days from 20 June to 22 June, Kim not only hosted Chinese President Xi Jinping in a state visit that granted the young North Korean leader tremendous legitimacy but also revealed the exchange of another set of “love letters” with Trump.

In a flash, we went from fears of provocation to the first movement on the moribund nuclear negotiations with North Korea in months. With Trump heading to Asia for the G20 summit and high-level meetings with Xi, Japan’s Shinzo Abe and South Korea’s Moon Jae-in, we’re likely to hear calls for a third Trump-Kim summit as regional leaders seek to build momentum for renewed talks with North Korea.

And despite the head-spinning speed of developments, none of this comes as a surprise. Here’s why.

Fleeing war in North Korea in 1951, my aunt and her siblings scrambled aboard an American cargo ship pulling away from port, her parents and grandmother shouting their names to keep track of them in the chaos of the evacuation. They made it. But their grandfather stayed behind in Wonsan to protect the family property.

He thought his family would return. They never saw him, or the rest of their family in North Korea, again.

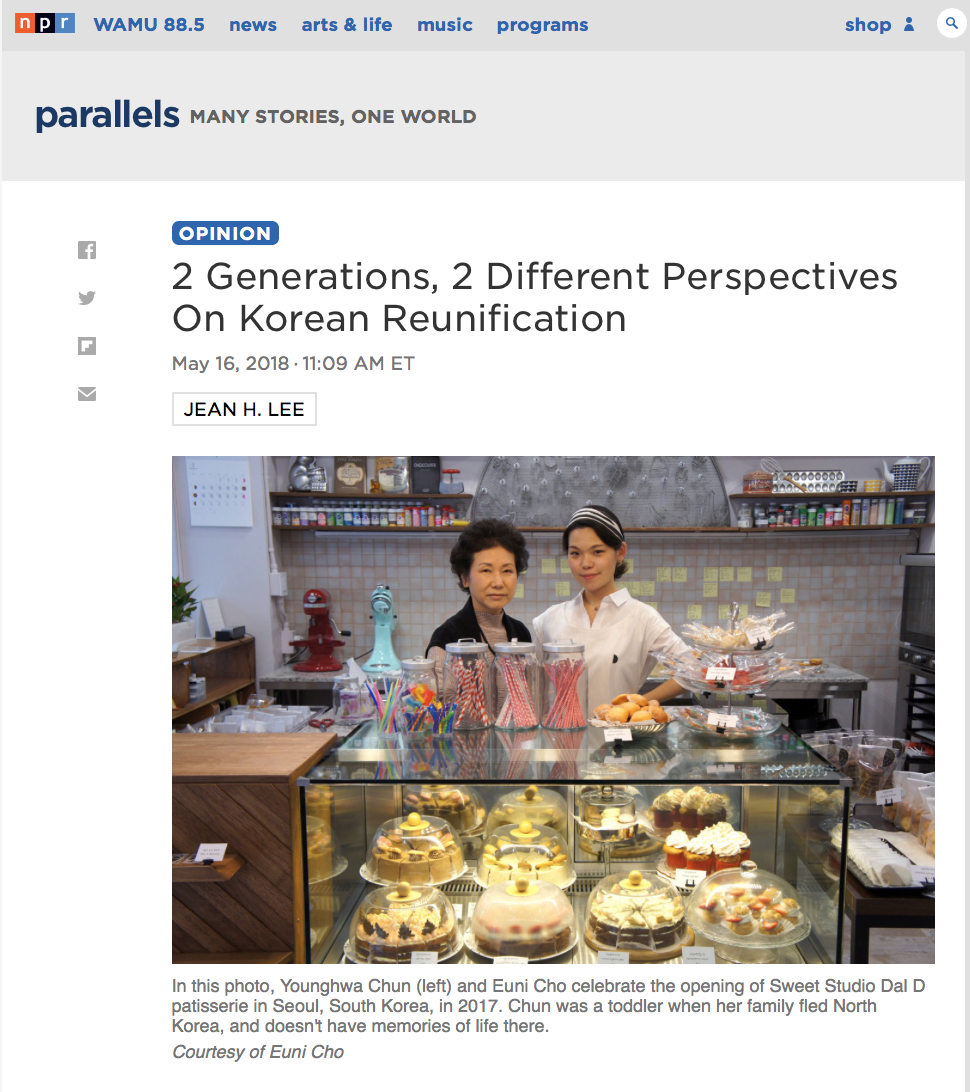

As the leaders of North Korea, South Korea and the United States discuss denuclearization and a possible peace treaty to formally end the Korean War of the 1950s, I wanted to check in with my aunt, a child of the war who was born in North Korea, and her millennial daughter Euni Cho, who grew up in democratic, thriving South Korea.

From bombs to Olympic banners: Can winter sports diplomacy stop a war in the Korean peninsula? North Korea's leader Kim Jong Un took the world by surprise with his announcement that his nation and South Koreawould unite under a single banner at the Winter Olympics. Was it a diplomatic masterstroke or a cynical stunt? Journalist Jean Lee pieces together what really led to this public relations coup.

North Korea’s participation in these Olympics runs the risk of rewarding bad behavior and handing Mr. Kim a diplomatic victory that he will brandish as proof that his strategy was right. Still, we have to start somewhere after so many years of tension.

Romance, humor, tension — everyone loves a good sitcom, even North Koreans. But in North Korea, TV dramas are more than mere entertainment. They play a crucial political role by serving as a key messenger of party and government policy. They aim to shape social and cultural mores in North Korean society. And in the Kim Jong-un era, they act as an advertisement for the “good life” promised to the political elite.

If President Trump thinks that his threats last week of “fire and fury” and weapons “locked and loaded” have North Koreans quaking in their boots, he should think again. If anything, the Mao-suit-clad cadres in Pyongyang are probably gleeful that the president of the United States has played straight into their propaganda.

While Kim Jong Un stares down his enemies abroad, it's easy to forget that he's also fighting a battle from within his own borders: to survive at all costs. Like any autocratic leader, he's under constant pressure to maintain order and allegiance. But his youth and inexperience make staying in power that much more of a challenge, which in turn requires absolute control. Opposition must be eliminated. No one is safe, not even his own family.

We in the United States often call the Korean conflict the “Forgotten War.” My high school history textbook in Minnesota devoted barely a paragraph to it, and growing up as the child of Korean immigrants, I knew almost nothing about a war my own parents survived as children. But the war is very much alive and present in North Korea, and the standoff with the United States figures prominently in their propaganda, identity, and policy.

After the 14th-century Korean ruler Taejo, founder of the Joseon dynasty, chose the youngest of his eight sons to succeed him, a spurned son killed the heir apparent and at least one of his other half brothers and eventually rose to the throne. Today, rumors of royal fratricide are again swirling, this time around the court of Kim Jong-un, the ruler of North Korea.

It was party time in Pyongyang. Workers scrambled to hang congratulatory banners in the lobby of the Koryo Hotel, my home away from home in the North Korean capital, where I was posted as an Associated Press correspondent. A gaggle of cooks, still in aprons and chef’s hats, dashed out from the kitchen to watch the festivities, and mothers tightened the pink bows in their daughters’ hair as the girls fidgeted in anticipation.

Two years after he made history by becoming the Navy's first black pilot, Ensign Jesse Brown lay trapped in his downed fighter plane in subfreezing North Korea, his leg broken and bleeding. His wingman crash-landed to try to save him, and even burned his hands trying to put out the flames.

A year after leader Kim Jong Un promised in a speech to bring an end to the "era of belt-tightening" and economic hardship in North Korea, the gap between the haves and have-nots has only grown with Pyongyang's transformation.

North Korean farmers who have long been required to turn most of their crops over to the state may now be allowed to keep their surplus food to sell or barter in what could be the most significant economic change enacted by young leader Kim Jong Un since he came to power nine months ago.

Her eyes well up when Li Pun Hui recalls her role in a historic example of "ping pong diplomacy."

"For 50 days, 24 hours a day, we lived together as one, trained together, slept in the same room and ate all our meals together," Li told The Associated Press at an interview in Pyongyang. "We shared the same food and our feelings."

For North Koreans, the systematic indoctrination of anti-Americanism starts as early as kindergarten and is as much a part of the curriculum as learning to count.

As the snow drifts through the towering evergreen trees, silence enshrouds this remote pilgrimage site, a place some here consider the Bethlehem of North Korea.

As North Korea celebrates the centenary of Kim Il Sung's birth, his past, like the misty peaks of Mount Paektu, remains veiled in myth.

If it seems as if North Korea wants us to sit up and pay attention — Don’t forget, we’re still building missiles and nuclear weapons! — that’s certainly one of its objectives.

But these tests are about a lot more.

Read More

My family’s wartime tale is not particularly remarkable; their harrowing experience could be told a million times over. This is not a tale of military heroism, or even one of selfless sacrifice. It is simply the story of one family of ordinary Koreans who survived the three cruel and crushing years of war that killed nearly a million South Korean civilians.

Read More

As other countries hurtle toward disaster, South Korea looks like the safer and smarter place to be. So what can other governments learn about how to handle coronavirus?

by Jean H Lee / March 27, 2020

Read More

Fleeing war in North Korea in 1951, my aunt and her siblings scrambled aboard an American cargo ship pulling away from port, her parents and grandmother shouting their names to keep track of them in the chaos of the evacuation. They made it. But their grandfather stayed behind in Wonsan to protect the family property.

He thought his family would return. They never saw him, or the rest of their family in North Korea, again.

As the leaders of North Korea, South Korea and the United States discuss denuclearization and a possible peace treaty to formally end the Korean War of the 1950s, I wanted to check in with my aunt, a child of the war who was born in North Korea, and her millennial daughter Euni Cho, who grew up in democratic, thriving South Korea.

Read MoreMeticulously choreographed military parades. Strident news announcements on state television. Missile tests presided over by a grinning Kim Jong Un. Propaganda from North Korea comes to us fully formed and almost alluring in its opacity: a finished product that has been carefully constructed to convey an idealized image of strength and unity.

Carl De Keyzer, a photographer based in Belgium, offers a different and more intimate view: a glimpse of the process of indoctrination within North Korea.

Read MoreWe in the United States often call the Korean conflict the “Forgotten War.” My high school history textbook in Minnesota devoted barely a paragraph to it, and growing up as the child of Korean immigrants, I knew almost nothing about a war my own parents survived as children. But the war is very much alive and present in North Korea, and the standoff with the United States figures prominently in their propaganda, identity, and policy.

Read MoreAt North Korea’s first party congress in 36 years, the country’s leader is showing why he’s the man to defend his people.

As delegates take their seats inside an elaborately festooned hall in Pyongyang this week, one question looms: What will happen at the Seventh Party Congress, North Korea’s biggest political convention in 36 years?

So cloaked in mystery is North Korea’s political machinery that very few details have emerged about the ongoing party congress, a rubber-stamp gathering of delegates that historically has served as a stage for the unveiling of key ideological movements put forth by the leadership. Major developments from this congress may not be revealed until the event ends in a few days’ time, if they are formally announced at all. (Foreign journalists brought in for a propaganda tour of the city were shut out of the congress hall.)

The significance of this event — the seventh party congress since the 1949 founding of the ruling Workers’ Party of Korea (WPK), and the first since October 1980 — is that it is leader Kim Jong Un’s big chance to hold court at his nation’s most important political gathering. The parts of his May 6 congress speech that have been released show Kim praising the “magnificent and exhilarating” of his country’s nuclear program — a program for which he is at least partially responsible. He will also be seeking to cement his place in history by outlining the policies and ideology that will define his era of leadership and serve as a blueprint for the country’s future.

For outsiders, it will be the best chance yet to decipher how this 33-year-old leader — who took power in December 2011 following the death of his father, then-leader Kim Jong Il — plans to lead his nation out of poverty and diplomatic isolation after a series of increasingly threatening nuclear provocations.

Kim, the third generation in the family dynasty to rule North Korea, will be leaning on the legacies of father Kim Jong Il and grandfather Kim Il Sung to legitimize his claim to leadership. The party congress is hewing closely to past precedent, but with a modern twist — making it helpful to look back at the 1980 congress, as well as previous congresses, to gauge what might be happening behind closed doors.

Foreign media accounts and history books contain scant information about what took place at the Sixth Party Congress, convened by then-President Kim Il Sung — though historians see it as the event where he officially anointed Kim Jong Il as the future leader of North Korea. In contrast, Kim Jong Il’s official biography — titled, simply, Kim Jong Il: Biography — provides a surprisingly cinematic and detailed account of Kim Jong Il’s alleged behind-the-scenes activities in the days leading up to the congress. According to the three-volume tome, which must be taken with a grain of salt as it is propaganda, Kim Jong Il proposed redrafting party rules to enshrine his father’s “Juche” philosophy — a homegrown ideology of self-reliance that combines Korean nationalism with socialism — as the defining feature of national identity.

The congress was also a massive spectacle. Looking at how the regime celebrated in 1980 will give us a hint to how this year’s festivities may unfold. According to his biography, Kim Jong Il’s vision for celebrations called for:

In the months leading up to the congress, Kim Jong Il also ordered a “speed campaign” calling on North Koreans to fulfill a year’s quota of work within 100 days, with a special focus on transforming Pyongyang into a “socialist fairy tale.” A second campaign called for the mass production of consumer goods — shoes, underwear, watches, cosmetics, and even refrigerators — to be distributed to the people during the party congress.

Back then, the 39-year-old and apparently indefatigable Kim Jong Il “greeted the dawn in his office” after staying up all night poring over congress plans. Then he inspected a construction project; directed a mass games dress rehearsal; visited the department store to examine new consumer goods; stopped by the Korean Central News Agency (KCNA), the state’s news agency; and surveyed new construction downtown. Even as the sun was rising on another all-nighter, Kim Jong Il — a notorious movie buff — managed to squeeze in a screening of a new feature film (the text doesn’t say which one). No surprise, then, that when the party congress opened a few days later, the future leader of North Korea looked “haggard.”

On the first day of the congress, Kim Il Sung gave a five-hour speech laying out the party’s successes. Delegates took the next day off for the million-people parade. Over the next three days, delegates adopted the revisions Kim Jong Il drafted that tweaked regulations about party leadership and expanded ideological education. Those regulations may sound insignificant or bureaucratic, but they helped further entrench the Kim family’s hold on power and solidified the nationalistic bent of the country’s political and economic system.

Indeed, party congresses have served as a stage for most of the defining moments in North Korea’s short but dramatic political history. The first congress — held in 1946, a year after Korea’s liberation from Japanese colonial rule — served as the inauguration of the WPK, which has ruled North Korea since its inception. The previous year, the Soviets had installed the 34-year-old guerrilla fighter Kim Il Sung as their man in Pyongyang. Contemporaneous photos show him smiling confidently in a Western-style suit and tie, with a version of the haircut Kim Jong Un sports today. It is no coincidence that Kim Jong Un, presiding over his own first party congress, put on a Western-style suit and tie on May 6 in favor of the Mao-style suit he typically wears. The references to his revered grandfather are deliberate.

The first post-Korean War party congress in 1956 formalized the importance of Kim Il Sung’s recently unveiled Juche philosophy. At the Fourth Party Congress, in 1961, Kim announced an ambitious seven-year economic plan. And at the Fifth Party Congress, in 1970, Kim Jong Il, then a party propagandist, instructed officials to distribute the first “loyalty” badges bearing Kim Il Sung’s image to delegates. The pins should be red, he allegedly said, to honor “the blood of the Korean communists,” and worn over the delegates’ hearts. Today, nearly every North Korean wears a now-iconic loyalty badge featuring Kim Il Sung or Kim Jong Il, or both.

Like his father and grandfather before him, Kim Jong Un ordered a “speed campaign” that had North Koreans toiling for 70 days and 70 nights to weave, plant, build, invent, and farm well beyond their yearly quotas. Like his father, he has been making the rounds to inspect a notebook factory and new construction in the capital. However, his guidance has also included overseeing the test-fire of a submarine-launched ballistic missile in April — a telling shift in priorities compared to his father.

Sixty years after his grandfather introduced Juche, Kim Jong Un will likely promote his brand of socialism, Kimilsungism-Kimjongilism (trust me, it sounds better in Korean). It’s an ideology that celebrates the contributions of both his father and grandfather, and cements his position as the third-generation heir to the Kim family dynasty. Party congresses have also been a chance to address factionalism, and to sweep out the old guard and bring in the new: North Korea watchers in Seoul speculate Kim will promote his younger sister, Kim Yo Jong, to a key party position as a way to further cement the Kim family’s hold on power.

More relevant for Americans, Kim Jong Un is expected to promote and further detail his vision for “pyongjin,” a two-pronged path of pursuingnuclear weapons alongside economic development. Indeed, Kim Jong Un’s special touch for this congress has been to bring nuclear bombs and ballistic missiles into the celebration. Without the 20 years of grooming his father had, the young leader needs a fast and powerful way to show he has the guts and vision to lead — and defend — his country for decades to come.

In the months following the October announcement of the Seventh Party Congress, the regime twice test-fired submarine-launched ballistic missiles, conducted a nuclear test, and launched a long-range rocket. A nuclear-tipped missile capable of threatening the United States is his political calling card, and the months of illicit and provocative nuclear and ballistic missile tests were part of a meticulously orchestrated plan to ensure Kim Jong Un arrives at the party congress in a blaze of glory. Indeed, Kim opened the congress by laying out the list of nuclear and ballistic missile successes.

It’s not surprising that North Korea went more than three decades without a congress. These are costly affairs for an extremely poor country — not to mention the human toll of the speed campaigns and mass games, and the deepening diplomatic isolation that accompanies each nuclear test. The bombs, the missiles, the parades, the performances, the construction: They’re all part of an investment the regime is making to enforce and inspire unity at home, and to ensure loyalty to a family determined to hold onto power for decades to come.

It was party time in Pyongyang. Workers scrambled to hang congratulatory banners in the lobby of the Koryo Hotel, my home away from home in the North Korean capital, where I was posted as an Associated Press correspondent. A gaggle of cooks, still in aprons and chef’s hats, dashed out from the kitchen to watch the festivities, and mothers tightened the pink bows in their daughters’ hair as the girls fidgeted in anticipation.

Read More“What is it like inside an American nightclub?” The question from a young North Korean woman startled me.

Read More

A North Korean woman poses for a photograph near Mount Kumgang, North Korea. Photo credit: Jean H. Lee. All Rights Reserved.

Communist North Korea is a world both foreign and familiar, a place where the men wear Mao suits and children tote Mickey Mouse backpacks, where they call one another "comrade" and love their spicy kimchi.

Read More

Download all episodes of The Lazarus Heist, watch Lazarus Heist animations, read our feature story about the hackers and view visualizations of the podcast episodes on Lazarus Heist homepage on the BBC World Service website!